Hello all—

It’s me, Gus Cuddy, and this is The Curtain_, a newsletter about theatre, arts, the internet, and sometimes the end of the world. You can read old issues here. And if you like it, you can consider subscribing here._

Today’s newsletter has some brief thoughts on the luxury of silence, before covering largely theatre-related topics.

I’m finally back in our apartment in Brooklyn after six months on the other side of the country. It’s been both strange and surprisingly normal to return to New York City; things feel different than when I left in early March, but not so much that it feels like a new place. Instead, it feels very much like an old friend that’s just undergone a few changes: masks everywhere, less crowded subways, and life spilling out onto the street from the indoors.

One of the biggest differences, coming from Northern California to New York City, is the noise. Where we live in New York, it’s difficult to completely retreat from noise (though our apartment faces away from the street). In Marin, we would step outside at night and look up at the stars and be able to feel the overwhelming silence. I’ve written about noise and silence before; silence has become a luxury in many different forms. The suburbs offer a particular type of silence, for instance: silence from the city noises, sure, but also another kind of silence, akin to plugging one’s ears to avoid hearing about what’s going on.

Because life is noisy in so many ways—the sounds of the industrial era and internet era ring in our ears—people often seek refuge. So silence has become an industrialized commodity, a lifestyle feature for those who can afford it: retreats into nature, guided meditations, sensory deprivation tanks. But what does silence actually provide? For some CEOs, it’s commercialized productivity. For others, it’s a blissful sense of ignorance. But sometimes, it’s for something more profound: silence has long had an association with the transcendent and the divine. This last type of silence is the most exquisite and deserving of our attention—but also the hardest to bring oneself to find these days.

# 🗒 notes from the Week

# “Solastalgia”

On a particular word for climate change-induced despair:

Eventually, Albrecht coined the term “solastalgia” — a neologism that combines the words nostalgia, solace and desolation — to describe their profound sense of loss and isolation, and the overwhelming feelings of powerlessness that came with it.

Solastalgia, as Albrecht defined it in a 2004 essay, is “manifest in an attack on one’s sense of place, in the erosion of the sense of belonging (identity) to a particular place and a feeling of distress (psychological desolation) about its transformation.” In short, it is “a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at ‘home.’”

# What Ben Brantley Stepping Down Means to the Future of Theatre

In somewhat of a surprise, the most influential critic in all of American Theatre decided to step down from his post this past week after holding the position of Chief Critic of the New York Times theatre section for the last 24 years.

The reactions to Ben Brantley’s departure have been mixed, to say the least. Many (often white) critics and peers have praised his work; many others, especially artists and/or people of color, have not.

Most of me is relieved to see that Brantley, who I frequently disagreed with, will not be the most powerful man in New York theatre anymore. (And yes, part of me is a bit sad we’ll no longer have an easy common enemy.) But I do think there’s one thing for certain: the position of Chief Critic for the New York Times theatre department is ridiculously over-powered. I hope that Brantley’s departure will have released some of that power, but I don’t think that will be completely true until the entire theatre industry is less top-down, more completely democratized.

Still, this is a no-brainer chance for the New York Times to hire a non-white-male critic who could have a significant role in shaping the future of New York Theater. They already have some good writers; I’ve enjoyed the work of somewhat recent addition, Maya Phillips, who writes about theatre, movies, and more. We’ll see what direction they go, but as long as this position holds the extreme power that it does, I hope they hire someone who can bring more people into the theatre, and whose artistic taste and sensibilities also match with the moment.

Further Reading:

Some Further Reading: My 2019 post on The State of Criticism in theatre.

# The tension between live and filmed theatre

As COVID-19 has forced many theaters to produce work online, it’s been fascinating to learn about the intricacies of this emergent new form: an online theatre-film hybrid—forms almost merging. Online theatre is not quite film, and it’s not quite theatre either—it’s something rather uncanny.

Creating theatre-to-be-filmed isn’t as simple as just “filming theatre”, and what works well on stage may not work well on screen-as-stage. Indeed, a director’s job in shaping a streamed/recorded theatre piece is fundamentally different from shaping a piece of live theatre. For one, the camera is didactic, controlling the viewer’s eye, whereas in live theatre the audience member’s eye is taking in the varieties of three-dimensional space.

Plays that have fundamentally theatrical senses of time and space may falter when presented virtually, as Helen Shaw writes about in her recent reviews of Three Kings, and In Love and Warcraft. Monologues like Sea Wall and Three Kings, in Shaw’s view, are more appropriate for this strange new medium than a play with many scenes that run on and on. I’m not sure I agree—or at least I don’t want the future of streaming theatre to be limited to talking head-style limited dramas—but I understand the point she’s making. There are large differences with how something is perceived through different mediums, especially when filmed theatre is one medium passed through another medium.

One of the biggest impediments with streaming theatre, though, is the labor agreements surrounding it in the US. It’s damning that Shaw is reviewing these UK productions, while big US theaters have largely faltered on getting much going. That’s primarily because of a lack of agreement between producers and Actors’ Equity on how actors can work in streaming theatre. There’s some understandable concerns surrounding safety, rights, and money—but it’s absurd that at this point this isn’t an easier thing. Theaters should be able to pay Equity actors to create streaming productions without much hassle, and they should be able to do it sooner rather than later. It’s the only way we’re going to be able to advance this new form and tease out the tensions between filming and live theatre.

Meanwhile: big Broadway shows like DIANA are allowed to create a filmed production for Netflix, before even opening on Broadway.

# How does theatre need to change?

The New York Times asked some of their critics about “how to birth a new American theater”. I especially appreciated the responses from Maya Phillips (open up the canon to forgotten writers of color) and Elizabeth Vincentelli’s (theaters should engage in a profit-sharing model).

Phillips quotes W.E.B. DuBois, from 1926:

The Negro is already in the theater and has been there for a long time; but his presence there is not yet thoroughly normal. His audience is mainly a white audience and the Negro actor has, for a long time, been asked to entertain this more or less alien group.

Not much has changed.

One point I’d like to add: if we want to open up the canon—which we definitely should!—then we also need a system that supports more strong young, diverse, creative directors, and enables them to tackle old plays. New York theatre simultaneously empowers both playwrights and a particular type of director: primarily the male, Euro-chic inspired one. (Theatre hangs on to dated ideas about the myth of male genius, enforcing power dynamics that put male directors at the top of the theatrical food chain.) I’ve written before about how there has been a proliferation of amazing playwrights in America recently (arguably more so than anywhere else in the world), but how New York still can’t trust anyone but white males to be “auteur” directors. (There are many amazing women directors—Rachel Chavkin, Rebecca Taichman, Whitney White, Danya Taymor, and countless more—but, for the most part, the industry doesn’t give them the same trust that their male counterparts are afforded.)

I’d like to see a future where a diverse set of directors are enabled to truly dive into older plays from playwrights that have been written out of the canon—and given the European freedom to not have total reverence to the text.

# ✂️ snippets from the week

In areas where COVID-19 hit hardest, rents in New York City have actually gone UP 😡 (Street Easy)

Black Scholars confront white supremacy in Classical Music (Alex Ross)

# End Note

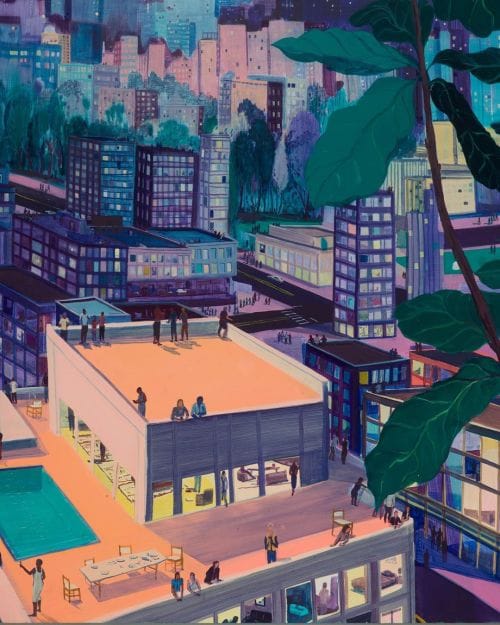

art by jules de balincourt

++

That’s all for this week! Thanks so much for reading. If you liked this, consider forwarding it to a friend.

You can reply directly to this email and I’ll receive it. So feel free to do that about anything. I love to hear back from people.

See you next time,

-Gus